Yosemite’s Ahwahnee hosted massive Thanksgiving feast. Unmasked guests had workers appalled.

As the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and California officials were urging Americans not to travel — and to keep celebrations small — over Thanksgiving, plans for a colossal feast were under way in Yosemite National Park.

“Prepare to be delighted with a Thanksgiving feast set in the historic Ahwahnee dining room,” reads an ad for the event on the Yosemite Mariposa County Tourism Bureau website. “Located in Yosemite Valley, the high ceiling and chandeliers create the perfect backdrop for a special occasion.”

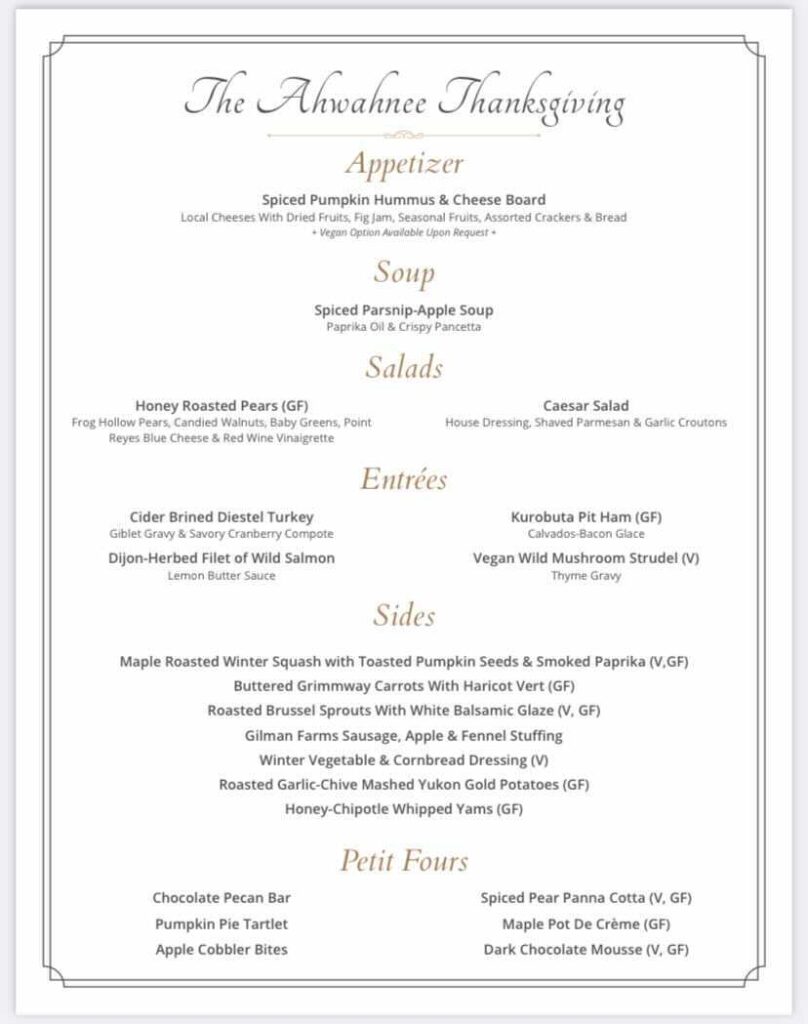

The menu included a touchless buffet, along with Cinder Brined Diestel Turkey and a Dijon-Herbed Filet of Wild Salmon. Advance reservations were highly recommended, according to the ad, due to “limited seating capacity.” The feast cost $103 per adult and $52 per child between the ages of 6 and 12; it was free for kids 5 and under.

According to hotel employees, the Ahwahnee was fully booked all week and hundreds of guests showed up for the dinner’s multiple seatings indoors from 2-8 p.m. Face coverings were, in theory, required, but there was no enforcement. While the limited seating and take-away options were meant to keep guests socially distanced, the bar area got extremely crowded, employees say, and social distancing fell by the wayside.

“Basically, everyone just did whatever they wanted, as if there was no pandemic,” says Lianne* Saylor, an Ahwahnee roomskeeper who was working during the event.

The hotel employees work for Yosemite Hospitality, a subsidiary of Aramark Management Services that’s contracted to provide hospitality services within the park. David Freireich, Aramark’s vice president of corporate communications, wrote in an email that he didn’t “have the exact seating info at my fingertips,” but that he knew the company was “below the mandates for reduced seating/capacity restrictions that were in place at the time.”

“The dinner itself was a touchless buffet, where staff, working behind plexiglass, plated the food for guests and handed it to them at the end of the line,” Freireich wrote. “For the health and wellbeing of everyone, we strongly encourage hotel guests to wear their masks and we provide social cues inside the hotels about the importance of wearing masks. To best of my knowledge, guests have been very respectful and wearing masks while inside.”

With COVID-19 cases exploding in California, employees say the Thanksgiving feast had them scared for their health, and for the vulnerable populations and health care workers living in neighboring communities. It was the culmination of what the park’s indoor service workers describe as an utter disregard for their safety, from both incautious visitors and their employer. Workers say they were incredibly relieved when the park reduced its hours and shut down accommodations and dining last week in response to California’s regional stay-at-home order.

Officials for the San Joaquin Valley region, where the park is located, launched a shutdown after ICU capacity fell below 15%; it dropped to zero percent over the weekend and has since remained precariously low.

Yosemite will keep its 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. schedule as long as the regional stay-at-home order is in effect, according to the park’s website. But after three weeks, if the San Joaquin Valley region were to increase its ICU capacity above 15%, accommodations and indoor dining could be reinstated in the park. Employees fear they could be placed back in harm’s way until President-elect Joe Biden, who has promised to initiate a mask mandate on federal property, is sworn in.

“We needed a federal mandate months ago,” Saylor wrote in a text message. “Thank God Biden will be making tourists wear one. Going to work and seeing all the tourists not wearing masks in crowds, indoors, has been extremely stressful and unsafe.”

Several of Saylor’s colleagues interviewed for this story expressed concern that speaking out would put their jobs at risk, and Saylor requested that we use her middle and last names. Beyond that, she isn’t holding back: “Thanksgiving was a f—ing s—show,” Saylor wrote in a text, referring to the number of unmasked guests. “It was awful … every bellman, bartender, server and roomskeeper … all were very concerned about possibly being exposed [to the virus].”

“I called the health department in Mariposa,” says another Ahwahnee employee who has worked several jobs in the hotel over the past decade. The employee spoke to SFGATE on condition of anonymity, because she did not want to jeopardize future employment.

The employee says management had her make preparations for 300 to 400 guests for the indoor Thanksgiving event. She tried to stay away from the guests, she says, because she was afraid of catching the virus.

Mariposa County’s Health & Human Services Agency “did hear about Aramark and Thanksgiving,” says Eric Sergienko, Mariposa County’s public health officer. And in a situation like this, the agency passes the information on to the park’s internal public health specialist, Sergienko says, who reminds the National Park Service of its responsibilities.

“Where [the park] can align with state guidance and health orders, they do that,” Sergienko says. But in some cases — for instance, with masks — the National Park Service must follow directives coming down from the U.S. Department of the Interior. Because the park is on federal land, and there has been no mandate for mask-wearing on federal property, visitors cannot be required — only encouraged — to wear them in Yosemite.

“We require, but cannot enforce mask wearing among [Ahwahnee] guests,” Freireich added.

Although park officials declined to respond to questions regarding what was being done to protect indoor workers, Public Information Officer Jamie Richards confirmed that “Yosemite does not require masks, but they are strongly encouraged.” By contrast, over at Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks, “masks or other face coverings are required to be worn inside all indoor and public spaces … this applies to both guests and employees,” according to the official website for the parks’ lodgings.

The inconsistency between national parks and vendors is a reflection of how the nation’s response to the pandemic has been fractured. Some national parks and vendors require and enforce masks, while others do not, depending on state and local ordinances.

Certainly there are other measures in place to prevent the spread of COVID-19 among Yosemite’s workers. Steve Wilensky, the founder of a nonprofit called CHIPS that connects people seeking employment with forestry jobs, has a couple of teams working in Yosemite. His workers, many of whom hail from the area’s indigenous communities, have their temperatures taken every day. They wear masks at all times. They keep distanced from one another and guests, though that’s easier to do while working outdoors.

“Of my 18 people who have been working in the park for the last month and a half, not a single person has tested positive,” Wilensky says. “And everybody has been tested a couple of times.”

How many park employees have had the virus and whether anyone was infected over Thanksgiving is not known. Park officials have been tight-lipped about the number of employees who have contracted the virus, citing HIPPA laws and privacy laws.

There is, however, another way of quantifying the level of risk people faced in the park over the holiday: sewage testing.

Back in May, Mariposa County teamed up with Biobot Analytics to monitor Yosemite’s wastewater for traces of the genetic material from Sars-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. Over the week of Thanksgiving, samples were collected from the El Portal and Wawona wastewater treatment facilities, which treat the park’s sewage in the western and southern areas of the park.

Sewage test results, which are measured in copies of the virus’s genetic material per liter of sewage, allow scientists to estimate how many infected people used the restrooms that feed the treatment plants. Over Thanksgiving week, multiple people with coronavirus — likely somewhere between seven and 35 — are estimated to have been in the park.

Here’s where the Ahwahnee employees lucked out: All of those infected people were seemingly staying (or at least using the restrooms) down south near the Wawona plant. Nearly an hour’s drive away, the El Portal plant — which handles all the wastewater from Yosemite Valley — showed a relatively low virus concentration that indicated less than one COVID-19 case per day. The Wawona sample, one other hand, showed a higher virus concentration than 93% of all samples submitted to Biobot for testing over the week of Thanksgiving and the five weeks prior, accounting for all seven to 35 suspected cases in the park.

“The people not wearing masks at the Ahwahnee were not infectious,” Sergienko hypothesizes. And down in Wawona, the accommodations are mostly condos and cabins that allow groups to isolate from each other, he adds.

Health officials aren’t permitted to share locations of COVID-19 patients, so we don’t know where transmissions around Thanksgiving occurred or if visitors were the culprits. But Sergienko did say that the county has seen infections inside of Yosemite that appear to have come from contagious visitors. Thanks to a highly successful contact-tracing program, which Mariposa collaborates on with the park, those cases have not seen onward transmission, Sergienko says.

“If we get a positive lab, we’ll find the person before 8 a.m. and be done with contact tracing by noon,” he says. “It was our biggest concern throughout the summer and into the fall: the introduction of COVID from visitors. It’s a careful balance. Our economy is dependent on tourism.”

At the hospital closest to Yosemite, John C. Fremont, administrators have scrambled to reconfigure the layout to maximize safety while creating additional space. There are now 16 beds for COVID-19 patients, according to a Facebook live presentation last week from Kenneth Smith, the chief of staff and chief medical officer, but the bottleneck is the number of available nurses to care for them.

As of Wednesday, one of those beds was in use. Of Mariposa County’s 181 cases since the beginning of the pandemic, 11 remain active. Four people have died, which is high in comparison with the national average. Health officials say this reflects the region’s older population, which exhibits more risk factors.

That’s one of the main things that worries Katy Imogene, who lives in El Portal and works in hospitality at Yosemite Cedar Lodge and Yosemite View Lodge. Both lodges were at or very near full capacity over the week of Thanksgiving, Imogene told SFGATE.

“It’s been ridiculous, the amount of guests from everywhere who are putting me, my family, and community at risk, so they can go on vacation,” she wrote in a comment in early December on Yosemite National Park’s Facebook page in response to a disturbing thread of comments downplaying the risks of the virus, the safety of the park’s employees and the importance of wearing masks. “Yosemite will survive the pandemic, it’s the people, especially the indigenous people, who make up Yosemite that need to be protected now.”

On Thanksgiving, there were signs at the hotel entrances asking people to wear masks while indoors, but “it wasn’t always happening,” Imogene says. She was working as a cashier that night, having “a constant stream of interactions with people from everywhere.” Rather than argue with the maskless, she adopted an approach of simply trying to get them “ordered and out of the way” as quickly as possible.

“Some people weren’t being considerate of each other,” she says. “It was distressing.”

Then there were the others, of course, who wore masks and empathized with the workers.

Los Angeles realtor Lisa Gild traveled from Los Angeles to Yosemite over Thanksgiving with her parents, her sister, her sister’s family and a man she’s dating. The group took COVID-19 tests before combining their bubbles, Gild said, and they maintained social distance with outsiders and wore masks. Still, they knew they were taking a bit of a gamble, particularly when they arrived in Yosemite Valley.

“The trails were pretty crowded,” she says. “I was there with my parents and they’re in their 70s. It was a little concerning.”

The group ordered food for takeaway at Degnan’s Kitchen and everybody was masked up in there, Gild recalls. But when they continued to the Ahwahnee for drinks, there were unmasked guests in the common indoor spaces, and the management wasn’t doing anything about it, Gild says. She expressed concern for the hotel employees.

“These poor people are risking their lives,” she says, “and they’re there to just make a living.”