California Sues Elk Grove Over Housing Project for Homeless

When developers in the California city of Elk Grove pitched two new housing projects last year, the proposals appeared to have much in common: Both would build new housing in a quaint section of the city affectionately known as “Old Town” for its attractive stretch of historic buildings.

One project was for people who could afford to purchase homes at the market rate in a state with some of the most expensive home prices in the nation. The other project was for people who were homeless. City officials approved the market rate project. But the homeless project has stalled as officials in the growing suburb of Sacramento argued it was not eligible to be fast-tracked under a 2017 state housing law.

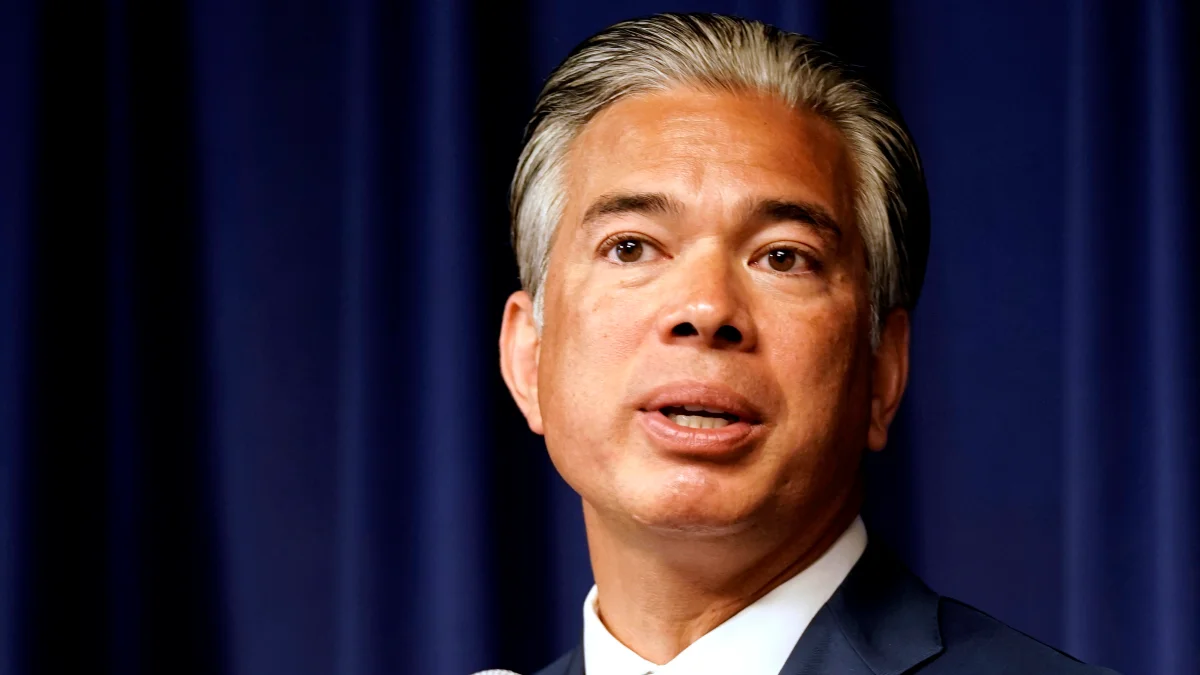

Monday, California Attorney General Rob Bonta and Gov. Gavin Newsom’s administration jointly sued the Elk Grove, arguing city officials broke the law by denying the project and accusing them of discriminating against low income families.

The lawsuit escalates a conflict between the state and local governments over how many housing projects cities should approve, and how fast they should build them. California, the nation’s most populous state, needs to build 2.5 million homes by 2030 to keep up with demand, according to the California Department of Housing and Community Development. But the state only averages about 125,000 new homes per year, almost two-thirds shy of what’s needed.

Newsom, a Democrat with potential presidential aspirations, and Bonta — a potential candidate for governor in 2026 — have been aggressively monitoring local enforcement of state housing laws. Last year, Newsom briefly withheld $1 billion in funding from local governments because he was unhappy with their plans to reduce homelessness. In March, the state sued the city of Huntington Beach and accused its leaders of ignoring state housing laws requiring them to build 13,000 new homes over the next eight years.

Monday’s lawsuit was different in that the dispute is over a single 67-unit apartment complex, signaling how far state officials are willing to go.

“That can seem small, but every time we say no to housing we make homelessness worse in California,” said Megan Kirkeby, deputy director for housing policy development for the California Department of Housing and Community Development.