‘My hands are tied.’ Bay Area 211 workers feel helpless in face of homelessness crisis

It started off as a routine call. But before Rico Millan knew it, the woman on the other end of the phone was crying.

She had phoned for help finding food pantries in Concord — making her one of hundreds of desperate people who dial 211 every day in the Bay Area, looking to connect to their county’s catch-all helpline. But as Millan asked more questions, the truth came out: the woman had moved to the Bay Area from Susanville, and it hadn’t worked out. Now, she was living in her broken-down Saturn, trying to get back home.

The worst part was, Millan couldn’t do much to find her a bed for the night. Space in shelters and affordable housing is scarce throughout the Bay Area. And the woman had a dog, making it exponentially harder.

He passed her information to Contra Costa County’s homeless outreach team. But, overwhelmed with demand on a Friday, the county said it likely couldn’t get to her until Monday.

“I remember texting my wife after I got off the call and telling her how crappy I was feeling,” Millan said. “Because I wanted to do more, but my hands are tied.”

People throughout California are told to call 211 if they need anything from shelter to mental health counseling to help paying utility bills. But as resources fail to keep up with the Bay Area’s staggering homeless population, it’s people like Millan who witness the pain of the crisis, dozens of times a day, every day. They try their best, lending a sympathetic ear and telling callers how to sign up for housing waitlists, check for available shelter beds, and access free food and other resources — sometimes providing assistance callers didn’t even think to ask for.

But there are more than 160,000 people without homes in California, and it never gets easier to disappoint someone who needs housing now.

“They really are hard to take,” said Steve Grimes, who answers 211 calls as a Contra Costa Crisis Center volunteer. “Because you want to help them. You don’t know if you’re really helping them very much.”

United Way Bay Area, which tracks 211 calls from people in Santa Clara, San Francisco, Napa, Marin, San Mateo and Solano counties, documented more than 72,000 calls and texts in the past fiscal year, up from 33,825 two years ago. In Contra Costa County, Millan answers between 35 and 40 calls a day — most of them seeking housing.

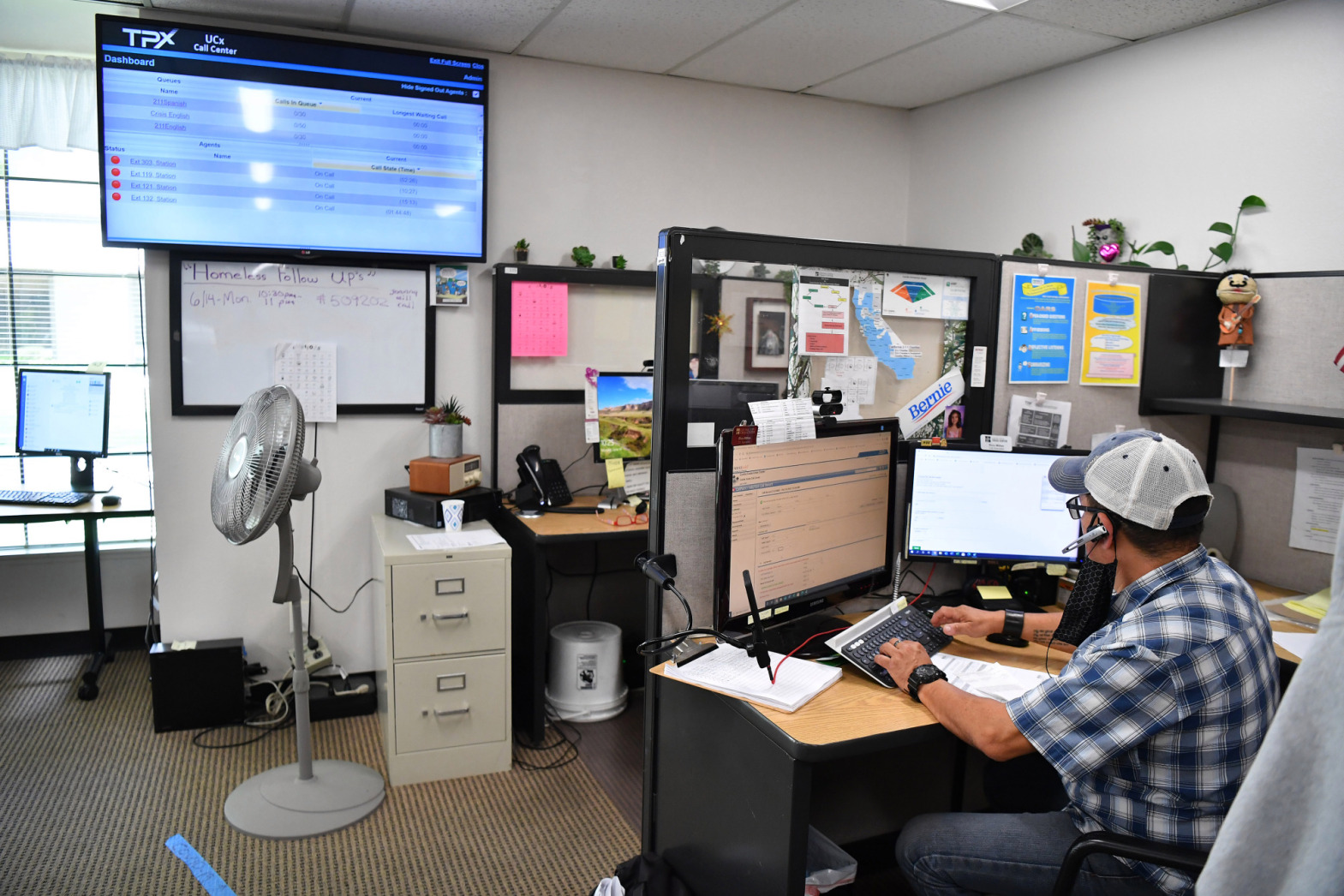

Callers are directed to different 211 centers depending on where they’re dialing from, and the workers who answer the phone have access to extensive databases of local health and social services programs related to housing, substance abuse, employment assistance, mental health and more. In some counties, the same call centers also take crisis calls from people contemplating suicide. They’re staffed 24/7, both by paid employees and, in some places, highly trained volunteers. While Alameda and Contra Costa counties have local 211 offices, others in the Bay Area outsource calls to Southern California.

The 211 system dates back to 2000, when the Federal Communications Commission created the three-digit dialing code as a nationally recognized helpline to save people the trouble of navigating a maze of services. Ventura County was the first in California to adopt the code in 2005, and Bay Area counties followed soon after.

But by 2012, United Way Bay Area was struggling with funding and had to shut down its San Francisco 211 center. Now, calls from San Francisco, Santa Clara, San Mateo, Napa, Marin and Sonora counties are answered in Ventura County. United Way keeps the database of Bay Area resources updated, and is in constant communication with their partners in Ventura, said Kelly Batson, chief community impact officer for United Way Bay Area.

Even so, the arrangement comes with challenges. Workers in the Ventura call center may not know basic Bay Area details, like BART doesn’t go to Marin County, or that South San Francisco is in San Mateo County, which makes it harder for them to suggest useful resources.

But if United Way Bay Area hadn’t outsourced its calls — a move Batson says saved the organization about $900,000 annually — its 211 service may have ceased.

“There’s certainly lots of advantages for local folks answering local calls,” Batson said. “But for us, we made the decision around it because we felt that 211 was an important service and we didn’t want to give it up, and we wanted to make sure it was still done well.”

The Ventura County specialists have dealt with their share of traumatic calls — many from the Bay Area or nearby. There was the time a domestic violence victim called from Monterey, only to have her husband start trying to beat down her bedroom door while she was on the phone. Or the time a victim of human trafficking called 211 from San Mateo County in the middle of the night, asking if Child Protective Services could take her two small children away, because they were no longer safe.

“There are times when it’s overwhelming,” said Julie Estrada, who answers 211 calls at the Ventura center, “and you do have to take a break just to regather your thoughts and be able to move on to the next call.”

The pandemic presented additional challenges. Call centers were inundated and wait times reached as high as two hours in some Bay Area counties, before coming back down. People can request a callback when demand is high, but unhoused people often use borrowed phones, making it hard to reach them.

Millan never found out what became of the woman sleeping in her car with her dog. Most 211 centers don’t have a good way to track outcomes, but Contra Costa is ramping up efforts to follow up with callers and record their results.

Last year, Millan answered a call from a homeless man at an Antioch gas station who needed help but didn’t have his own phone. Millan contacted the county’s homeless outreach team, described the caller — an older man in a wheelchair wearing an orange safety vest — and asked them to send a team right away.

After Millan ended his shift, he happened to drive by that very same gas station. The man in the wheelchair was still there, sitting in the middle of the parking lot so the county workers wouldn’t miss him. It had been hours since he’d called.

Moments like that leave 211 staff feeling gut-wrenchingly helpless.

But it’s the other calls — the ones that give someone hope — that keep them coming back to work each day.

During a recent shift at the Alameda County 211 center, Elsa Gonzalez took a call from an Oakland man who was sleeping in his car after losing his job. He wanted a housing voucher. Gonzalez couldn’t give him one, but she explained how he could find a shelter bed for the night, and told him how to get on the county’s housing waitlist.

Calling Gonzalez ma’am, he thanked her and explained he’d never asked for help before, but he was willing to do whatever it took to get back on his feet.

“This is a big step for me,” he said. “I really appreciate this.”

After she hung up, Gonzalez put a hand over her heart.

“That was good,” she said, smiling. “That was a good call.”