These Bay Area residents vanished and have never been found

Walk around Berkeley today and you’ll see her face: a smiling young woman paired with the word “MISSING.”

Sydney West wrapped up a summer session at UC Berkeley and went to visit San Francisco on Sept. 30. She was last seen near Crissy Field and hasn’t contacted loved ones since. Her face is ubiquitous around Berkeley streets, the latest sad reminder of a family that now lives with uncertainty every day.

According to FBI statistics, more than 609,000 missing person reports were filed by law enforcement agencies in the United States last year. The vast majority — 99.7% in 2019 — are found. But some linger, fading year by year, and are never solved.

The Charley Project, a website that tracks cold case disappearances, lists hundreds of missing Bay Area residents spanning decades of police records. Some drew little attention, even at the time of the person’s disappearance, while others became massive national stories. Several became literal poster children for “stranger danger,” the panic around non-family abductions that swept America in the 1980s.

Below, we’ve detailed nine of the Bay Area’s most confounding missing persons cases — all still open and still unsolved.

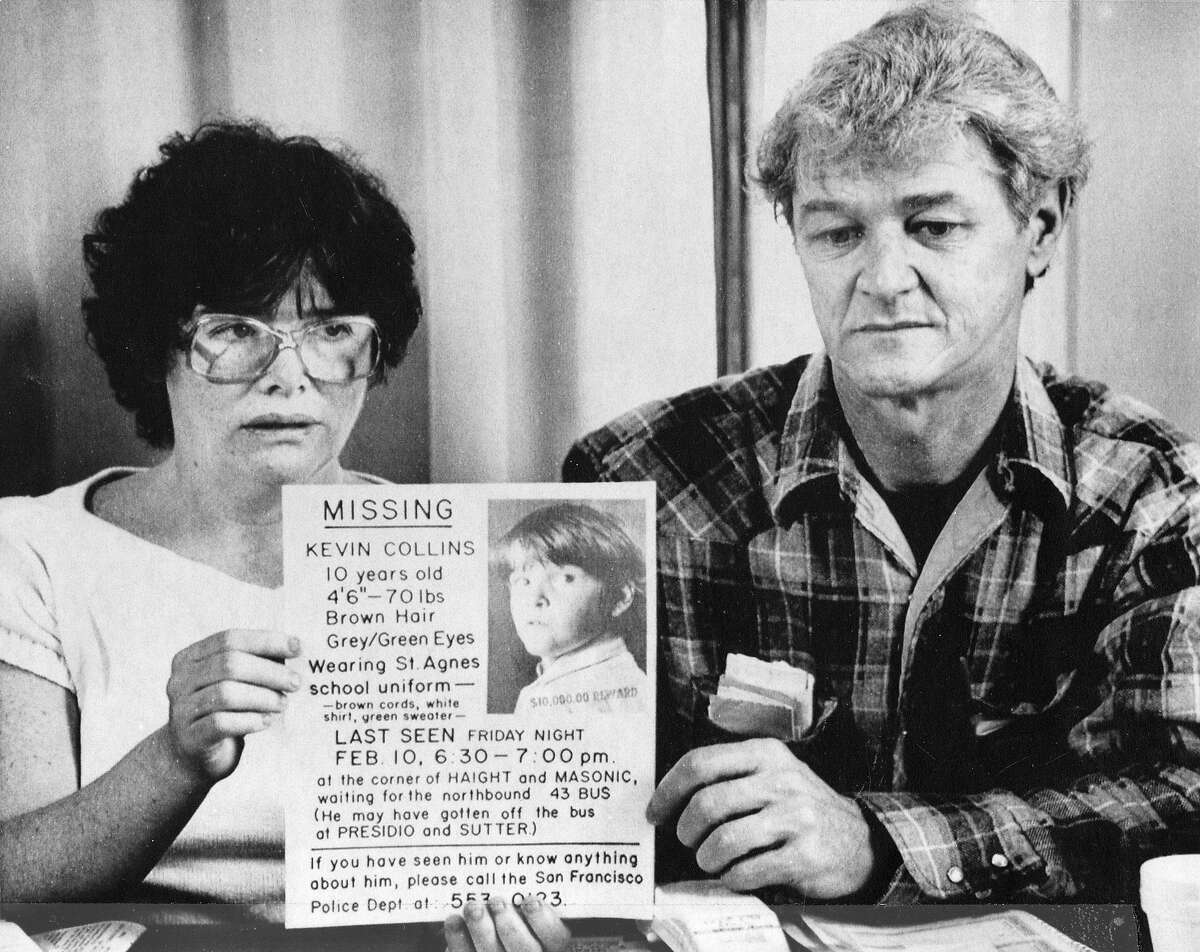

Kevin Collins was a shy fourth grader. The sweet, gap-toothed boy was quieter than his eight brothers and sisters, but a happy kid. His older brother Gary was at home sick on a cold evening in February 1984 and couldn’t accompany Kevin to basketball practice at the Saint Agnes School gym on Page Street. So after practice, Kevin waited alone for the 43 bus on Oak and Masonic to take him to the family home on Sutter Street.

A blonde-haired man with a black dog was seen talking to Kevin that evening at the bus stop. Kevin would never make it home.

Posters of Kevin covered San Francisco. The local news, and soon national news, picked up on the story, as the ’80s wave of high-profile child abductions made parents across America think twice about letting their children out alone. Kevin became one of the first missing children to appear on milk cartons and billboards. His young face, glancing over his shoulder in black and white, made the cover of Newsweek, under the ominous headline: “Stolen Children: What Can Be Done About Child Abduction?”

But one of the most publicized searches for a missing child in U.S. history yielded no results, and the case went cold.

In 2013, SFPD reopened the case and informed Kevin’s family they had a viable suspect — a convicted pedophile named Wayne Jackson who lived on Masonic, near where Kevin was last seen. Jackson was questioned in 1984 but never arrested.

Investigators had recently discovered that Jackson also went by several other names, including Dan Therrien. Therrien had a lengthy criminal past in both California and Canada, including serving six months in jail for a felony charge of lewd acts on a 7-year-old child. He was also arrested in 1973 for allegedly kidnapping and sexually assaulting two 13-year-old boys.

Therrien went on the lam, moved to San Francisco and changed his name. He had a black dog at the time of Collins’ disappearance.

Jackson died in 2008, but authorities have reportedly tried to offer his partner, who lives in Canada, immunity to tell them what he knows, so far with no results.

San Francisco police searched the home on Masonic, just one block from the bus stop, where Jackson lived in 1984. After cadaver dogs found a scent, the authorities took jackhammers to concrete slabs in the garage. Several bones were removed, but they turned out to be from a small animal.

“This case is a case that haunts the San Francisco Police Department,” Police Chief Greg Suhr said at the time.

The case remains open.

Anyone with information on this matter is asked to contact the SFPD Major Crimes Unit at 415-553-1145.

—

The next wave of “stranger danger” cases came not long after, dominating Bay Area news and terrifying parents across the region. Three of the most high profile were the disappearances of Amber Swartz-Garcia, Michaela Garecht and Amanda “Nikki” Campbell. The details of each are as follows:

Amber Swartz-Garcia, 7, was jumping rope in the front yard of her Pinole home in June 1988 when she disappeared. Multiple witnesses over the years recalled seeing a young girl forced into a car by a man, but these tips ultimately amounted to nothing.

In 2009, police announced they were closing the case after a confession by Curtis Dean Anderson. Anderson, a cab driver, was arrested after 8-year-old Midsi Sanchez escaped his grasp several days after he kidnapped her. Anderson was convicted in Sanchez’s kidnapping and of the murder of 7-year-old Xiana Fairchild of Vallejo. Once in prison, he confessed to several more crimes, including the murder of Amber Swartz–Garcia.

Due to Anderson’s obsession with attention, many suspected he was adding additional murders to his tally in order to increase his notoriety. Due to outcry from Swartz-Garcia’s family, Pinole police reopened the case in 2013. Anderson died in prison in 2007.

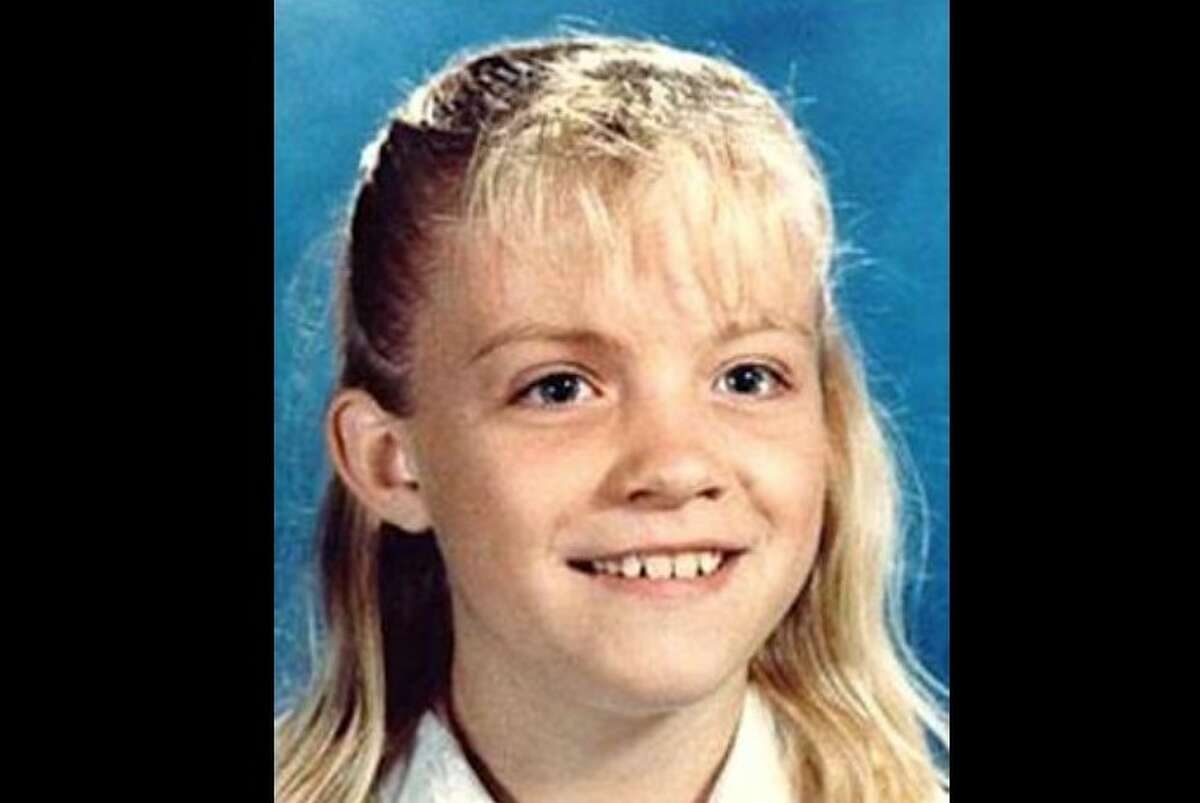

Michaela Garecht, 9, and a friend rode their scooters to a market two blocks from home in Hayward on Nov. 19, 1988. After making their purchases, Michaela realized her scooter was missing. She spotted it in the parking lot and, when she went to retrieve it, a man waiting in the adjacent car leaped out, grabbed her and drove off.

The case became a staple of the nightly news and crime shows like “Unsolved Mysteries.” Over the years, nearly every infamous child killer in California has been probed for links to Michaela’s disappearance — none leading authorities any closer to finding the missing girl.

The most compelling suspect is Loren Herzog, one half of the Speed Freak Killers duo. Along with Wesley Shermantine, the pair are suspected in the murders of up to 70 people. Herzog was paroled in 2010 after an appeals court threw out his convictions. He killed himself in 2012, allegedly shortly after he was told that Shermantine was working with authorities to show them where the bodies were buried. After his death, Shermantine noted Herzog looked very similar to the suspect sketch of Michaela’s kidnapper. Searches of Herzog and Shermantine’s burial site in Linden, Calif., did not uncover evidence linking either man to Michaela.

Amanda “Nikki” Campbell, 4, was biking to a nearby friend’s home in a quiet Fairfield neighborhood on Dec. 27, 1991, when she disappeared. A search found her bike a few blocks away and police dogs tracked her scent to the I-80 onramp more than a mile away. It is believed she was snatched by a stranger.

Curtis Dean Anderson was floated as a suspect in Nikki’s disappearance, although no clear links were ever established. Another man, Timothy Bindner, also became a person of interest for police because of his contact with the families of Michaela and Amber.

Bindner approached both the Swartz-Garcia and Garecht families offering help with their cases. Investigators asked Amber’s mother to maintain contact with him in the hopes he might reveal more. But ultimately, the only thing police could accuse Bindner of was being overly interested in the families of missing children — odd, certainly, but not a crime.

In 1997, Bindner won a defamation lawsuit against the city of Fairfield after he was named a suspect in the Nikki Campbell case.

Anyone with information about these three missing girls is asked to contact the San Francisco FBI office.

—

You’ve likely never heard of Charla Maria Ghost.

She would be 49 today, but hasn’t been seen since the day after Christmas 1990, when, as a 19-year-old in a black-and-white polka dot jacket, black jeans and Puma sneakers, she vanished from the streets of Oakland. And that’s really all we know.

What makes Charla’s story so important is not that it’s unique; it’s that it’s so common.

Charla is a member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe, one of the federally recognized indigenous tribes in South Dakota and a branch of the Lakota people.

A recent U.S. Department of Justice report revealed that American Indigenous women face murder rates that are more than 10 times the national average. One in three Native women is sexually assaulted during their life, and 67% of these assaults are perpetrated by non-Natives.

In a report earlier this year, the Sovereign Bodies Institute found that crimes against Indigenous women often fall into jurisdictional gaps in the system, leaving victims and their families without recourse. Problems include the misclassification of race (scrawling “white” or some other assumption based on appearance in the “race” column), and the labeling of many deaths as accidental, despite the evidence to contrary, which the study calls a “a chronic and pervasive failure to investigate.”

The FBI doesn’t even have comprehensive data on how many Indigenous women are murdered or missing.

In response to this epidemic of violence, the Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women (#MMIW) movement has drawn attention across North America in recent years.

Regional grassroots efforts, the elevation of the issue on social media and the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women’s Memorial March (now in its fifth year) have compelled many U.S. states to take steps toward passing legislation confronting the issue.

Charla may never be found, but there’s finally the chance that simply being an Indigenous woman in America will not mean your life is severely more endangered than anyone else.

—

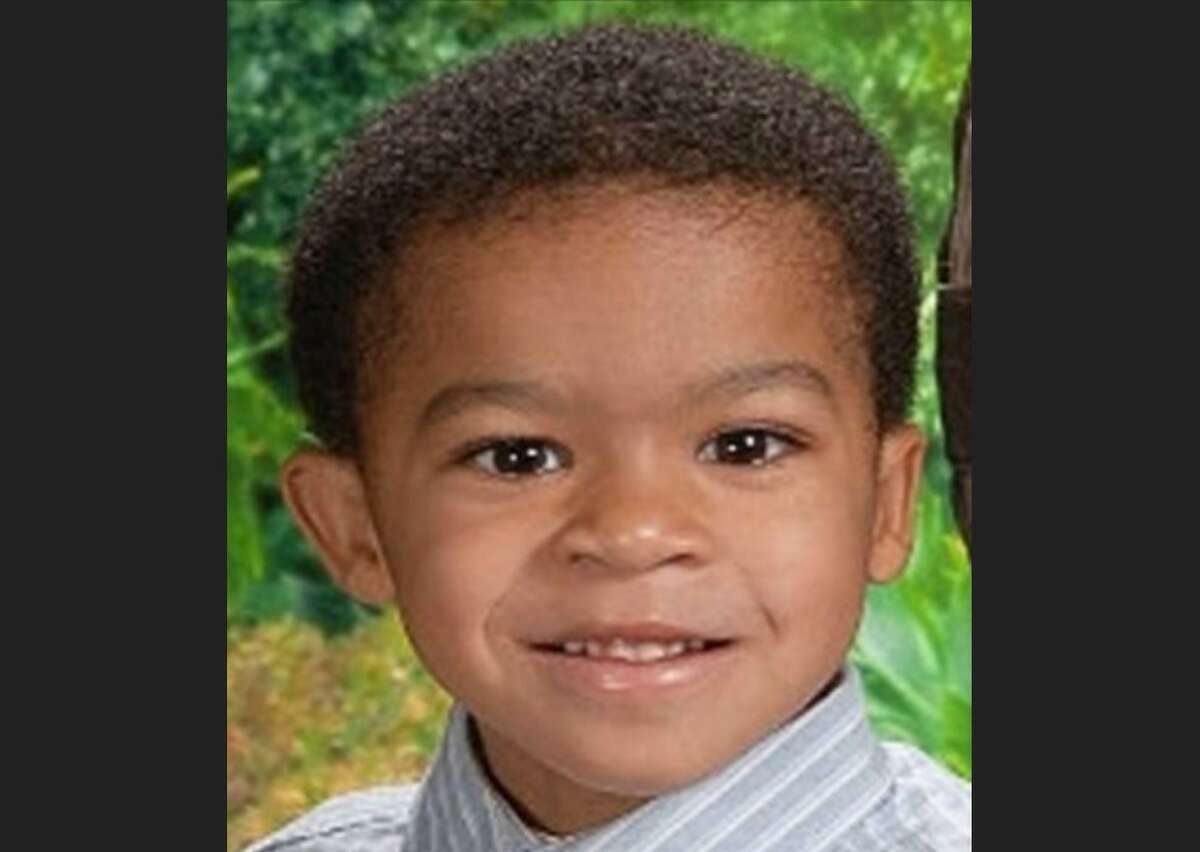

Some say 5-year-old Hassani Campbell was last seen on Aug. 10, 2009, on College Avenue, the busy shopping district in Rockridge, Oakland. Others say he disappeared days before that.

Hassani’s foster father, Louis Ross, says he was dropping Hassani and his baby sister Aaliyah off with his fiancee — the children’s aunt and foster mom — Jennifer Campbell.

Jennifer managed the Shuz shoe store (now Pony Studios and Salon), at 6012 College Ave. Louis says he left Hassani in his BMW in the Shuz parking lot as he carried baby Aaliyah around to the front of the store. When he returned, Hassani was gone.

An extensive search of the area found no sign of Hassani, who suffered from cerebral palsy and would have been unable to travel far alone.

Most of the doubt surrounding this case, and Ross’s testimony, concerns the fact that the foster father appeared to have misgivings about raising a disabled child. Authorities alleged that Ross sent an angry text to Jennifer 10 days before the disappearance, threatening to abandon Hassani on a BART platform.

Police immediately doubted Ross’s story — Hassani supposedly disappeared in the middle of a crowded business district, but nobody saw anything unusual and tracker dogs could not find the child’s scent.

No other witnesses recall seeing Hassani in Rockridge, and police determined the last time the child was seen by anyone other than his foster parents was Aug. 6, at a Walmart in Fremont near where they lived.

After Ross failed a polygraph test, and Jennifer refused to take one, both foster parents were arrested on suspicion of murder 18 days after Hassani’s disappearance. Both were released after prosecutors decided there was insufficient evidence to file charges.

Authorities are no longer actively searching for Hassani, stating they simply don’t know where to look. Although Ross and Jennifer maintain he was abducted from Oakland, police continue to name his foster parents as prime suspects in Hassani’s disappearance. Ross and Jennifer ended their relationship less than a year later and moved from their Fremont home. Hassani’s case remains unsolved.

Anyone with information about the case can call the Oakland Police Department 510-777-3333.

—

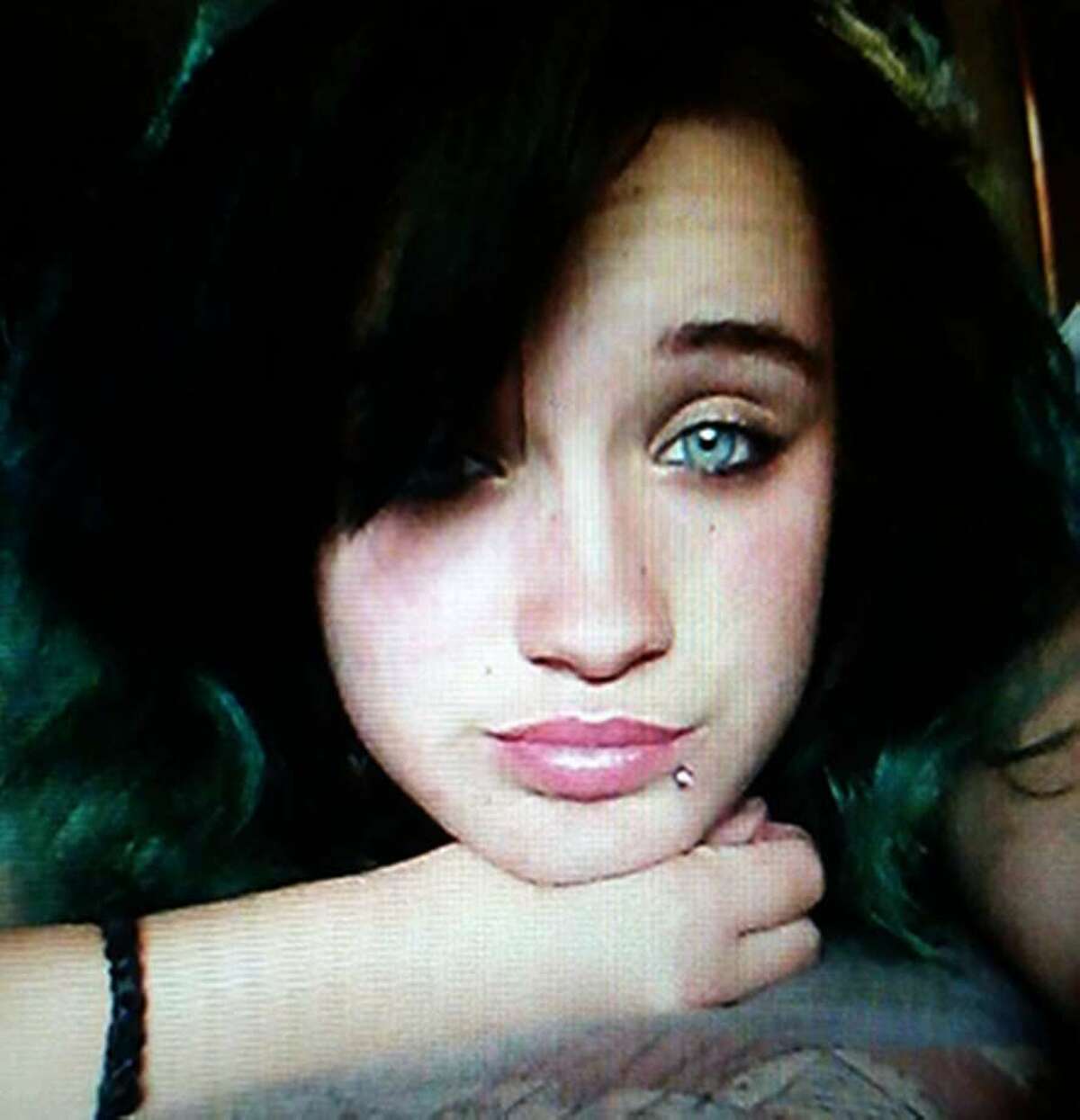

Fifteen-year-old Pearl Pinson was making her way to school on Wednesday morning, May 25, 2016, when she was attacked by an armed man.

Witnesses said the man dragged her across the pedestrian overpass, where Home Acres Avenue meets Interstate 780 in Vallejo. Her face was bloodied, she was screaming for help. Witnesses heard gunshots, including her brother William, also walking to school a few blocks away. The man bundled her into a gold 1997 four-door Saturn.

By the time the police arrived she was gone, and Pearl hasn’t been seen since.

An acquaintance of Pearl’s, Fernando Castro, 19, was quickly identified as her suspected abductor. Rumors spread that Fernando and Pearl were in a relationship, but after scouring Pearl’s phone and social media, and talking to her family, police could not confirm this fact. Pearl’s sister Rose said he had been seen roaming around their neighborhood.

Thanks to an Amber Alert, Castro’s vehicle was sighted the following day in San Luis Obispo County, over 250 miles south of Vallejo. The California Highway Patrol chased Castro into a residential area, where he abandoned his vehicle and ran into a mobile home near Solvang, on the Central Coast.

The occupant of the home escaped unharmed, as Castro attempted to steal a car and began shooting at police while driving away. The authorities returned fire and killed Castro. A small amount of Pearl’s blood was found in the trunk of the car, but she was nowhere to be found.

The whereabouts of Castro and Pearl over the preceding day led authorities on a search that spanned hundreds of miles of California. Security footage showed Castro’s vehicle at a Bodega Bay gas station, 50 miles northwest of Vallejo. Dozens of law enforcement officers searched a 25-square-mile area in the region in the following days, but nothing was found.

Theories on Castro’s motive for Pearl’s abduction vary from sex trafficking to gang activity to a domestic fight, but four years later there are still no answers, and no sign of Pearl.

Her sister Rose told the Daily Republic in 2017 that she often dreams of her sister. She remembers her smile and the times they shared doing each other’s hair, nails and makeup. She said Pearl thought about becoming a firefighter or veterinarian.

Rose said she wishes the authorities had gotten some information from Castro before they shot him dead and holds hope that her sister is alive but is scared about what may have happened to her.

“If they find her alive, she’s not going to be the same,” Pinson said. “She won’t be herself, having gone through so much. I’m kind of scared to see what happens.”

Anyone with information about the case can call the Solano County Sheriff’s tip line on 707-784-1963.

—

It’s one of the stranger and more obscure missing persons cases in Berkeley. Virgie Baliton, then 41, was in town for UC Berkeley’s May 2017 commencement ceremony. Baliton, a live-in caretaker, was with her employer of 14 years, an 80-year-old woman. The two lived in Hong Kong and flew out to see the elderly woman’s granddaughter graduate.

The morning of graduation, Baliton and the woman’s family went to Cafe Strada across the street from the Cal campus. While there, Baliton got up to use the restroom. Finding it closed, she told her group she was going to search for another open bathroom nearby. She never returned.

Calls to her phone went to voicemail and Baliton’s employer’s family says they were unable to reach Baliton’s relatives in the Philippines. Her employer believed her to be happy with her job and expressed particular concern due to Baliton’s lack of familiarity with the United States.

Anyone with information regarding her case is asked to contact UCPD at 510-642-6760.

—

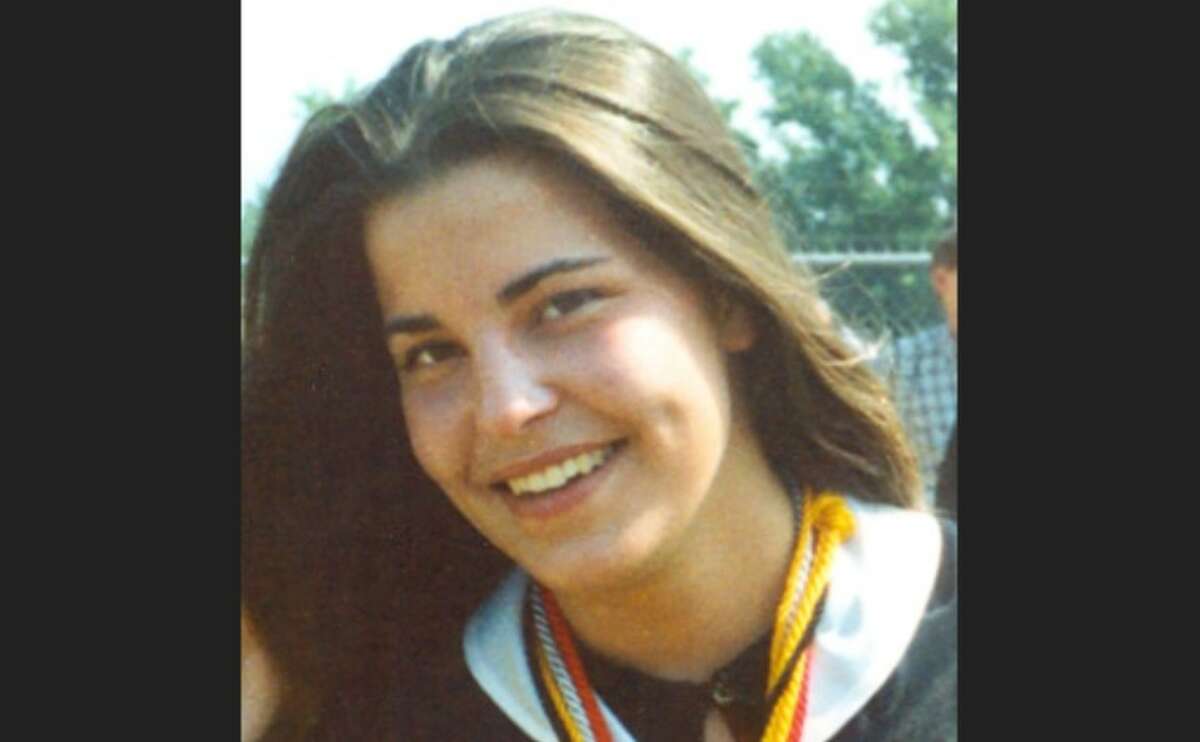

In terms of baffling cases, few have stuck in Bay Area memories as powerfully as Kristen Modafferi.

Modafferi was an 18-year-old college student working at a coffee shop in the Crocker Galleria in downtown San Francisco. After wrapping up her afternoon shift on June 23, 1997, she walked out of the mall and was never seen again.

The scant clues were each more mysterious than the next: a sighting of her walking with an unidentified woman in the mall, a Bay Guardian found in Modaferri’s trash with a personal ad circled (“FRIENDS: Female seeking friends to share activities, who enjoy music, photography, working out, walks, coffee, or simply the beach, exploring the Bay area! Interested, call me,” it read.), a scent trail tracked by bloodhounds to the Sutro Baths.

The case went cold until 2018, when investigators working with the Modaferri family announced they’d found a potential lead. They said a cadaver dog alerted to a possible crime scene at 274 Jayne Ave. in Oakland, the rental where Modaferri was living at the time of her disappearance. The private investigators speculated Modaferri may actually have returned home to Oakland and went missing from there, and they alleged that police failed to check the home next door, which they say was a halfway house at the time.

No further leads have been found at the Jayne Avenue home, and the case remains open.

Anyone with information is asked to contact the San Francisco FBI office.