While most Bay Area economies floundered in the first year of the pandemic, Santa Clara County’s soared

When the pandemic shut down wide swaths of the country in March 2020, the economies of all Bay Area counties tanked — except for Santa Clara County’s.

Unlike counties such as San Francisco and Napa whose financial health suffered in large part because they lean heavily on tourism and service industries still feeling the lingering effects of shutdowns, Santa Clara County thrived, according to newly released federal data.

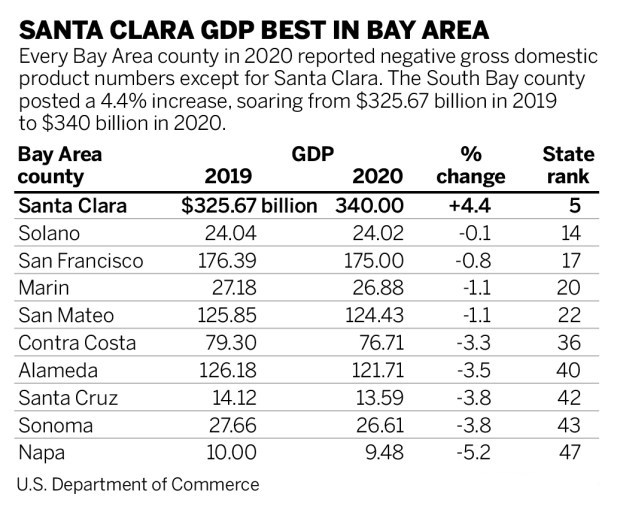

While every single Bay Area county and California’s largest counties, such as Los Angeles, San Diego, Orange and Sacramento, reported negative gross domestic product (GDP) numbers in 2020, Santa Clara County posted a 4.4% increase, from $325.6 billion in 2019 to $340 billion.

And nationwide, Santa Clara County’s performance was just as remarkable. Among what the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis defines as large counties — those with more than 500,000 residents — Santa Clara recorded the largest increase in the country.

Local economists attribute Santa Clara County’s outlier performance to the cluster of high-tech industries that have made it their base. Technology was one of the very few industries that didn’t skip a beat during the pandemic, and many of the larger companies have boasted record profits.

“Santa Clara County has the highest concentration of tech employment by far of any county or metropolitan area in the United States,” said Steve Levy, director of the Palo Alto-based Center for Continuing Study of the California Economy. “And that’s been true for a long time.”

Statewide, Los Angeles County reported a -6.3% GDP, Sacramento -2.8%, San Diego -2.9% and Orange -4.4%.

The GDP — which measures all goods and services produced within a region from the physical like a cheeseburger to the digital like a Facebook ad — is considered a barometer of an economy’s health.

Positive numbers usually indicate that companies are hiring, Levy said, but a higher GDP doesn’t necessarily translate into more money for a county because income taxes paid by companies and employees go to the state and federal government.

He and other local economists say that although many tech companies are headquartered in other Bay Area counties like San Mateo and San Francisco, it’s their intense clustering in Santa Clara County that makes the real difference.

The county is home to trillion-dollar companies like Apple and Google, as well as those worth hundreds of billions of dollars like Meta (formerly Facebook), Nvidia and more recently Tesla, which moved its headquarters in December to Texas but still employs thousands of people in its Palo Alto offices and Fremont car production plant.

How the county’s tech companies function today also gave them an advantage during the pandemic, Levy said.

Silicon Valley used to build physical products like semiconductor chips, he said, but that manufacturing has been moving to countries like Taiwan and South Korea, as well as other parts of the country. Last month, for example, Samsung announced plans to build a $17 billion chip factory near Austin, Texas.

Instead, Levy said, the tech companies that remain in Santa Clara County are much more service-oriented, offering digital products like Zoom, whose use increased dramatically during the pandemic and whose employees were easily able to shift online.

In addition, the county is not as reliant on industries that were slammed by the pandemic, said Sean Randolph, senior director of the Bay Area Council Economic Institute. He pointed to Napa, which had the largest decrease in GDP during 2020, as a region that relies heavily on tourism and the restaurant industry.

And even though San Francisco has some technology companies like Salesforce and Airbnb, the drop in international tourism offset the positive growth those corporations provided, he said.

“I think the tech companies in San Francisco did as well as they did in Santa Clara County, but they don’t have the same density and scale for the most part that they do in Santa Clara,” Randolph said. “And then you have the counterbalancing factor that the hospitality sector is so large (in San Francisco). And they did the worst in any sector here across the country.”

While the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis’ county GDP numbers are delayed by a year, both Levy and Randolph said they expect 2021’s numbers to look similar to 2020.

“If you figure that tech continues do very well — there’s been so many IPOs (initial public offerings), and you look at all the venture investment, from that standpoint, it has been just an extension of 2020,” Randolph said. “Then you flip to the other side. The tourism story is the same. Tourism is not recovered or it’s very slightly recovered. There has been an uptick in tourism for sure, but it’s mostly domestic.”

The numbers seem to contradict the ongoing narrative of tech companies fleeing California for cities like Austin, whose three counties did show GDP increases between 0.5% and 2.7% during 2020.

But Levy thinks the “Texodus,” as it’s come to be known, is overblown. While the federal government’s 2021 data may show a better picture of how the winds are blowing, he pointed out that California is still posting record levels of venture capital money and big tech companies like Meta and Apple are leasing huge amounts of office space.

But the spectacular wealth Santa Clara County has experienced since the beginning of the pandemic also raises questions about the area’s ongoing inequality crisis.

In February, the 2021 Silicon Valley Index released by San Jose-based nonprofit Joint Venture Silicon Valley’s Institute for Regional Studies, found that income inequality in the region “has grown twice as quickly as that of the state or nation over the past decade.”

Sixteen percent of the region’s households hold 81% of the area’s wealth, while the region’s bottom 53% held only 2% percent of “investable assets,” according to the study.