Tech companies are striving to utilize nuclear fusion in unprecedented ways

Long considered an unattainable goal, the idea of using nuclear fusion to power homes, businesses, vehicles, and even airplanes is now seen as a real possibility by scientists and engineers, with the potential to fundamentally transform global energy consumption.

“It’s tremendously exciting because we would essentially have unlimited power,” said Carl Bass, chairman of Alpha Ring, a company developing miniature nuclear reactors to harness fusion power. “It will happen in our lifetime – the real question for me is just the scale at which it happens.”

Around the world, more than 40 companies – including several in California – are exploring over 20 different methods to harness fusion, believing it to be a cleaner and potentially more affordable energy source. This race to harness fusion comes as fossil fuels, known for their contribution to climate change through pollution, continue to dominate energy production.

“We could produce energy at a fraction of the cost with almost none of the problems of the current energy infrastructure,” Bass explained. “You could envision a small reactor in a vehicle, certainly in a boat or a ship – almost anywhere we need to use heat or electricity, we could produce it differently and much more cleanly.”

Alpha Ring’s approach, regarded as unconventional in the industry, is known as “electron-catalyzed fusion.” This method relies on what the company describes as “miniaturized” nuclear reactors, designed to be small enough to fit on a tabletop yet powerful enough to supply entire communities with energy.

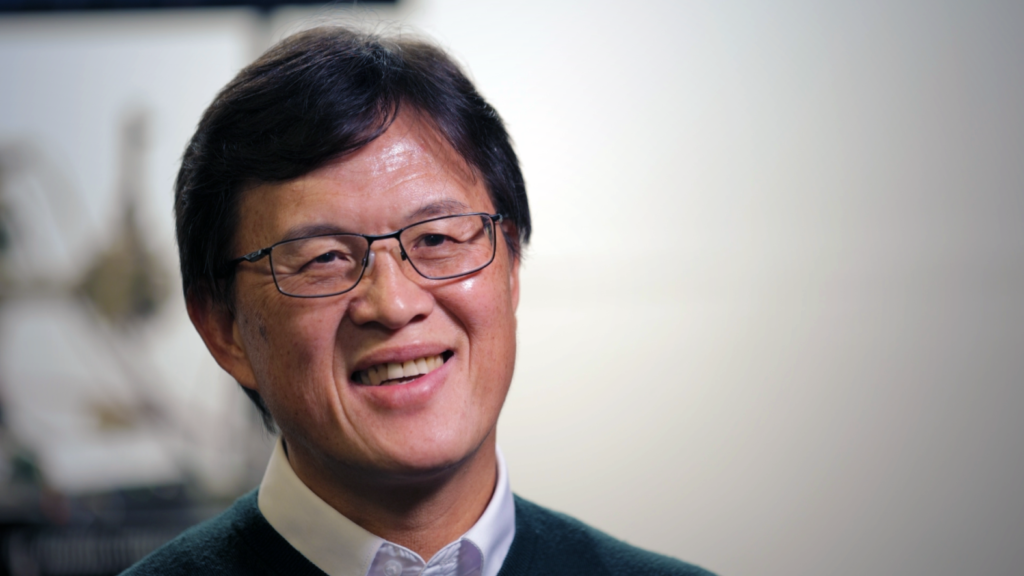

Steve Hwang, Alpha Ring’s chief operating officer overseeing the company’s laboratories in Monterey, Los Angeles, and Taipei, describes the technology as very complex. He believes that if they can produce abundant energy, it will be a game-changer.

Despite the potential benefits, a significant challenge remains: no one has yet been able to make nuclear fusion a commercially viable and sustainable energy source. Fusion, a process where atoms are fused together to release energy, is the same process that powers stars like the sun. In contrast, nuclear fission, currently used in more than 50 nuclear power plants in the U.S., involves splitting atoms and can produce harmful radiation.

One of the key advantages of fusion is that it does not emit carbon or radioactive waste, and the materials required for the reaction are abundant worldwide. While unlocking the ability to harness nuclear fusion has long been a mystery, scientists believe we are closer than ever to achieving this goal.

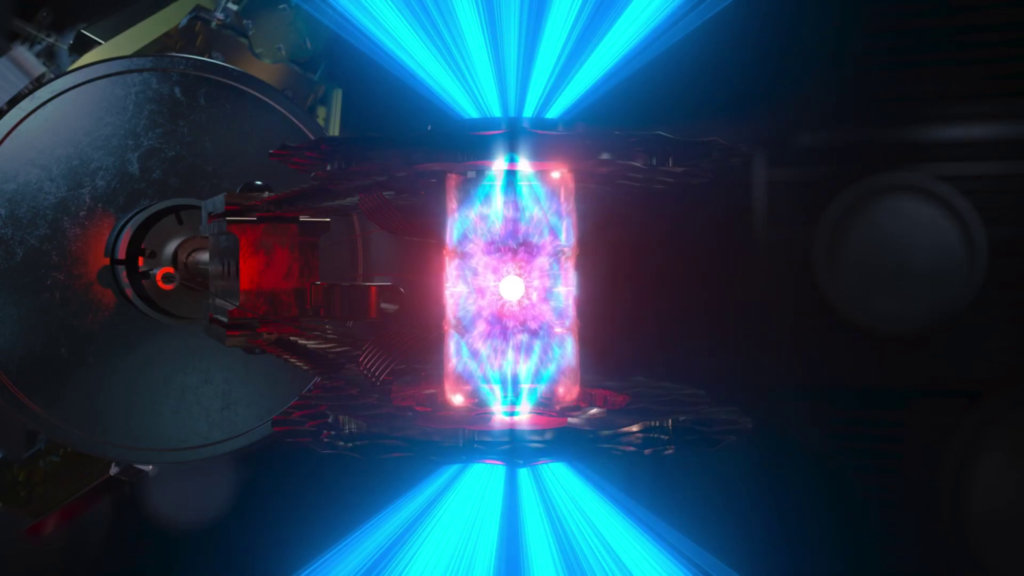

Physicist John Edwards, a senior advisor at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and former director of its Inertial Confinement Fusion program, believes it’s not a matter of if, but when we will achieve commercial fusion power. He was part of the team that achieved the first-ever nuclear fusion reaction inside a lab in December 2022, where more energy was produced than what it took to initiate the reaction.

This milestone was achieved using 192 lasers to create temperatures exceeding 180 million degrees Celsius, six times hotter than the sun’s core. While these successes are significant, the amount of energy produced has been minimal, and the reaction duration has been extremely brief.

To be commercially viable, the fusion process would need to generate about 100 times more energy, according to Edwards. Additionally, the frequency of reactions would need to increase significantly. Edwards believes that achieving these goals will require collaboration with the private sector, as it is a consumer product that will require private industry involvement to become a reality.

Private companies attracted $6.2 billion in investments last year to address the nuclear fusion challenge, according to the Fusion Industry Association, representing over 100 companies engaged in fusion experimentation or supporting the industry, including Mitsubishi Corp. and Google. This marked a $1.4 billion increase from the previous year.

Andrew Holland, CEO of the association, noted the shift from government-led efforts to private industry taking on nuclear fusion as a potential revenue source within the typical 10 to 15-year timeline of a venture capital fund. He anticipates the emergence of “pilot plants” over the next 15 years, which would be the first to integrate fusion-generated energy into the power grid, enabling the process to provide electricity for homes and businesses.

However, Berkeley Professor Ed Morse, an expert in nuclear fusion, remains cautious about tech companies’ claims of solving long-standing scientific challenges. He advises skepticism, suggesting that while some concepts may be viable, others may be less credible.

Alpha Ring, for instance, claims to have achieved over 15 nuclear reactions in its labs, with energy outputs sufficient to power a light bulb overnight. Although the duration of some reactions has surpassed 19 hours, much longer than those achieved at the Livermore lab, Bass acknowledges the skepticism surrounding such claims. To substantiate its findings, Alpha Ring plans to submit its research to various scientific journals for review, aiming to demonstrate the reproducibility of its nuclear fusion reactions and their potential to revolutionize energy production on Earth.