Air pollution drops as countries shut down amid spread of COVID-19

It’s a surreal sight: Webcams from across Italy show normally packed tourist destinations, streets and beaches empty, scenes that seem more aligned with a movie than real life.

In the battle against COVID-19, countries around the world are restricting gatherings, encouraging people to work from home and closing public venues. Italy is under lockdown.

All of these actions are having quantifiable consequences, particularly in our environment, scientists believe.

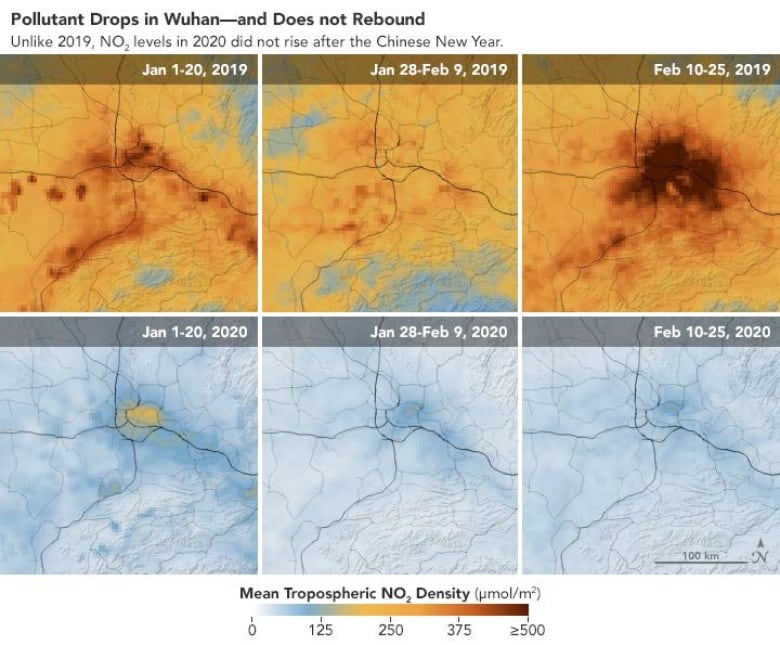

The change was first noticed over Wuhan, China, the city that first reported incidents of the new coronavirus that leads to the COVID-19 disease.

Satellite observations found that nitrogen dioxide (NO2) levels had dropped by 10 to 30 per cent between Jan. 1 and Feb. 25. NO2 emissions are produced by cars, trucks and power plants, among other human-related activities. While NO2 is also produced naturally, it accounts for just one per cent of total emissions.

“This is the first time I have seen such a dramatic drop-off over such a wide area for a specific event,” Fei Liu, an air quality researcher at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, said in early March.

While some of the reduction was linked to Chinese New Year celebrations, when many people were on holiday away from work, what surprised scientists was the fact that, after the holiday, NO2 emissions did not rise.

But that wasn’t the only thing that had dropped. Particulate matter 2.5 (PM 2.5), a fine particle in the atmosphere linked to serious health issues, was also reduced.

This is particularly good news for those living in China. The country has some of the worst air pollution in the world, which is responsible for killing more than one million people annually. The United Nations estimates that globally, roughly four million people die each year because of air pollution.

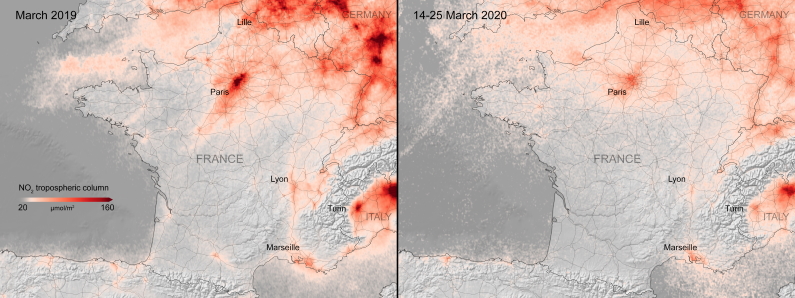

Changes over northern Italy

Meanwhile, other observations by a satellite gathering information for the European Commission’s European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecastsshowed a significant NO2 drop in northern Italy.

Copernicus ECMWF@CopernicusECMWF

The #CopernicusAtmosphere Monitoring Service has observed a roughly 10% per week reduction in NO2 concentrations in northern Italy since mid-February. But what does that really mean, and how can we detect it using satellite data?

Find outhttp://bit.ly/2wduzwl #COVID192824:13 AM – Mar 17, 2020Twitter Ads info and privacy154 people are talking about this

Because of its geographical location, Italy’s north — which includes the region of Lombardy, home to the country’s second-most populous city, Milan — is considered one of the worst cities for air pollution in Europe.

The European Space Agency (ESA) also used the Copernicus satellite to measure NO2 over Italy. It found that NO2 decreased by 10 per cent since the lockdown began in the region.

“When you look at satellite data, if you look at the time series of nitrogen dioxide, you always see northern Italy as a kind of hotspot,” said Claus Zehner, a scientist with ESA who works with Copernicus data. “We have a lot of pollution, a lot of industry and also the location [matters].”

But under a national lockdown, with most businesses closed and people relegated to being shut in, there were far fewer vehicles on the road, meaning less NO2 being pumped into the air.

Lessons to be learned?

With the concern over the climate crisis, some are wondering if this is a teachable moment.

“This is a big question that very many people are asking themselves these days: What can we learn from this pandemic or this crisis that the world is going through now?” said Kristin Aunan, a researcher at Norway’s Center for International Climate Research.

“Will we learn from it and take measures to see how we can avoid getting back to normal for things that we would like to avoid?”

While not everyone is able to work from home, she noted, it could make organizations consider allowing those who can to do so.

“Hopefully we will at least change your habits in some important ways that could lead to a longer-term reduction in emissions,” Aunan said.

Zehner echoed that sentiment.

“You could also do some theoretical measurements or predictions — if you say we will change all our cars to electric cars where we do not get any of these kinds of emissions. And then you could even calculate what would be the impact,” he said, likening it to a test case “to check what can be done if it would change our habits.”

As to what these lowered NO2 emissions might mean in terms of CO2, Zehner said we’ll have to wait and see.

“You should also see reduction of greenhouse gases over this timeframe. But it’s very hard to get how much,” he said. “This would have to be investigated in detail. And this will be done. There will be publications on this for sure. People are working on it already.”